Bright lights shine on an unfolded, handwritten letter in Art in Print’s dark photo studio in the Zeeland Archives in Middelburg, the Netherlands. Buzzing softly, the scanner moves over the 17th-century letter, whose contents were still hidden in an intricate folding format only seconds before. Not only the photographers are present, but also the curator from the Dutch Museum voor Communicatie and the conservator from the American research institute MIT, as well as the conservator of the Zeeland Archives. They are breaking new ground…

The letter is part of a large collection of approximately 2600 pieces of correspondence, which was preserved for centuries in a 17th-century trunk covered with sealskin. In 2014 the international project team “Signed Sealed & Undelivered” (SSU), was established. Thanks to funding from the Dutch Organization for Scientific Research (NWO) and support from the Museum voor Communicatie in The Hague – the current owner of the letters – the team embarked on an unprecedented task: making 2600 pieces of mail accessible, of which 600 are still unopened.

The museum is glad the letters now receive the attention they deserve, because they harbor a wealth of historical information. In fact, the total number of letters can still easily rise to about 3000, because some pieces of mail hold even more letters within them.

After the digitization, the project’s researchers can start working on the contents of the letters. The SSU project team consists of Rebekah Ahrendt, Assistant Professor in musicology at Yale University, Nadine Akkerman, lecturer in early modern English literature and culture at Leiden University, Jana Dambrogio, Thomas F. Peterson (1957) Conservator at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) Libraries, Koos Havelaar, Curator of Postal History at the Museum voor Communicatie, David van der Linden, researcher and lecturer at the University of Groningen in The Netherlands, and Daniel Starza Smith, researcher at Lincoln College, University of Oxford.

Valuable Pieces of Correspondence

The trunk with undelivered mail was owned by postmaster Simon de Brienne. Born in France as Simon Veillaume, he styled himself Lord of Brienne. In London he first served Prince Rupert of the Rhine, son of the Winter Queen, but around 1669 he came to The Hague. He received an influential position at the court of Stadholder William III, and in 1676 acquired the lucrative office of postmaster of Brabant, Belgium, France and Spain.

Strikingly, from 1686 he shared his postmastership with his wife, Maria Germain (died 1703), making it one of the few offices officially held by a woman in the 17th century.

In the past, the recipients of letters paid postage and delivery charges. Undelivered letters therefore represented value. That’s why the Briennes kept these undelivered letters in the trunk, which is now part of the collection of the Museum voor Communicatie in The Hague. The letters are written in French, Spanish, Latin, Italian, English and Dutch.

At the time no envelopes existed, so letters had to be folded in such a way to become their own sending device. One side of the paper held the letter’s contents, while the other side – after an often complicated method of folding – held the address and seals. Besides the contents of the letter, the writing paper still harbors a wealth of information, such as stamps, seals, postmarks and letterlocking formats. Moreover, the paper’s watermark – a mark that is specific to the papermaker – tells us more about the origins of the paper.

Digitization Everything but Ordinary

The digitization of the letters in the “Signed, Sealed, & Undelivered” project is anything but ordinary. To begin with, the 600 unopened letters will remain sealed, although tests are underway at Queen Mary, University of London, to make the contents visible using special X-ray techniques and software.

For the digitization of the ca. 2000 opened letters and the exterior of the 600 sealed letters the project team enlisted the help of photo studio Art in Print, located in the Zeeuws Archief in Middelburg, The Netherlands. And with good reason, because the digitization of the opened letters isn’t ordinary either. That has everything to do with Jana Dambrogio’s research at MIT Libraries, specializing in letterlocking, the technology of folding and securing a substrate such as paper to function as its own envelope.

Diamond-Shaped Letter

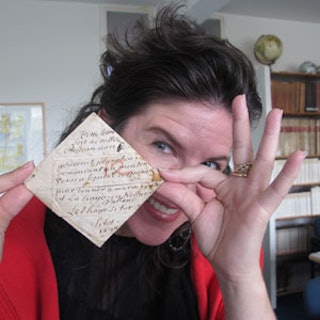

Jana Dambrogio holds up a small folded letter. “Astonishing how small it is,” she says smiling, while she picks up a second, seemingly identical letter. “This one seems to be folded in the same manner, but on the inside it’s entirely different.” She explains that there are approximately 14 different basic letterlocking formats. The postal trunk from The Hague contains no fewer than 6 of the 14 folding formats. “And within each letterlocking format, some 25 interior variations can exist.”

The conservator specializes in the letterlocking techniques of late medieval and early modern post. In her research on the letters from The Hague she hopes to find a relationship between folding formats and the letters’ contents. “Take this letter with a black seal,” she says. “It’s is a mourning letter. And this letter, folded in a diamond shape, is a love letter. To what extent does the folding format say something about the person who wrote the letter? It would seem that the more secret the contents, the more steps had been taken to build physical security into the folded letter.”

Thus, the folding format is essential to her research, but how to record that digitally?

Visible from Ink to Fold

Ivo Wennekes and Mark van der Graaff are photographers at the photo studio Art in Print. From March to May 2016 they scanned the ca. 2000 letters that already had their seals broken, as well as the exterior of the 600 letters that are still sealed. The digitization was financed by Metamorfoze, the national program for preservation of paper heritage of the Dutch ministry of Education, Culture and Science, housed in the Koninklijke Bibliotheek (Royal Library) in The Hague. Since the start of the program “Metamorfoze for Archives” in 2005, the two photographers have been helping with the digitization projects of the Zeeland Archives and many other heritage organizations.

Wennekes is trained as a professional photographer and initially specialized in the photography of artworks. “That’s all about the correct reproduction of color, texture and material,” he says. Van der Graaff is an artist himself: “It is important to have control over the recordings, not only with artworks, but also with archival records. We keep control over the reflection and texture in our scans.”

The letters in the “Signed, Sealed, & Undelivered” project demand a specific scanning method. Dambrogio says,“The folds have to remain visible during scanning. Not only the written contents, but also the visual information about the carrier matter – in this case, the folds in the paper.”

Wennekes explains, “That means that the textures have to be made visible by scanning with the utmost control over light balance.” Because of the strict Metamorfoze guidelines there is just a little leeway. “Within these boundaries we need to find a way to make the folds visible.”

For the photographers, this project produces a groundbreaking collaboration with the American research institute MIT. Van der Graaff: “Michael Tarkanian, a senior lecturer in the Department of Materials Science and Engineering, and Jana Dambrogio are developing a method to scan documents as evenly as possible. We have tested this system and are helping to develop it further.”

Folds and Conservation

The folds in the paper are an important starting point for document research, and therefore also for conservation. Sylvia Rietbergen, restorer at the Zeeland Archives, agrees with this: “Originally, restoration focused just on text, and only later on the material on which the text was written and the construction of the material. For a long time, paper documents were drastically restored. After restoration, a letter appeared as new again, even the folds were sometimes invisible. Now we are much more cautious.”

The Brienne project emphasizes how important it is to preserve the carrier in its original form as much as possible. All visible traces will be preserved, both the specification of the postage by the postmaster as well as the paper creases where the writer folded the letter. When the letters from the postmaster’s trunk are too damaged to be scanned, Rietbergen performs a small repair. In the end hardly any repairs were carried out on the Brienne letters.

Permanent Place in the Museum

By now, the trunk and the letters assume a special place in the life of Koos Havelaar, Curator of Postal History at the Museum voor Communicatie. He has been working with the collection since 2010. First, he assisted with the doctoral research of Simone Felten, a Ph.D. student who sadly passed away in the summer of 2013. He then helped two researchers, SSU team members, Rebekah Ahrendt and David van der Linden.

The trunk with letters has become invaluable to the Museum voor Communicatie. In the future, after the museum’s reopening in 2017, the history of the postmasters, the trunk, letters and the project will receive a permanent place, both in the museum’s display and online on the museum’s website.

But there is more in store. “It will be followed by a transcription project via crowdsourcing.” In the future, the public can contribute from home, transcribing the contents of the letters behind their computer and rewriting them into contemporary Dutch. “I hope it will work out, because the majority of the letters is written in a foreign language,” Havelaar says.

Thanks to the trunk, we have also learned more about the postmaster’s profession. “Besides the letters, part of the administration was also preserved,” Havelaar explains. “In fact Simon de Brienne was not too closely involved with the work of postmaster. He held the position, but left the execution to others. Oftentimes he was not even living in The Hague.”

The Briennes were employed by Stadholder-King William III. After his takeover of England, Scotland and Ireland – known as the Glorious Revolution – the couple remained in London for more than ten years, usually in Kensington Palace. Thanks to the archival records, we know a lot about the court life of the postmaster and mistress. “Only the faces of Simon de Brienne and Maria Germain remain a mystery,” Havelaar says. “We have not been able to find any portraits of the couple.”

Further reading

- Projectwebsite Signed Sealed & Undelivered

- Museum voor Communicatie, Nieuws: eerste resultaten en Topstuk: de postkist van de Haagse postmeester De Brienne en Geheimen 17e-eeuwse brieven eindelijk onthuld (all texts in Dutch)

- Metamorfoze, Ongeopende zeventiende-eeuwse brieven scannen (Dutch)

- Jana Dambrogio en Daniel Starza Smith on Letterlocking

- MIT Libraries, Research into letterlocking

Translation: Anna de Bruyn