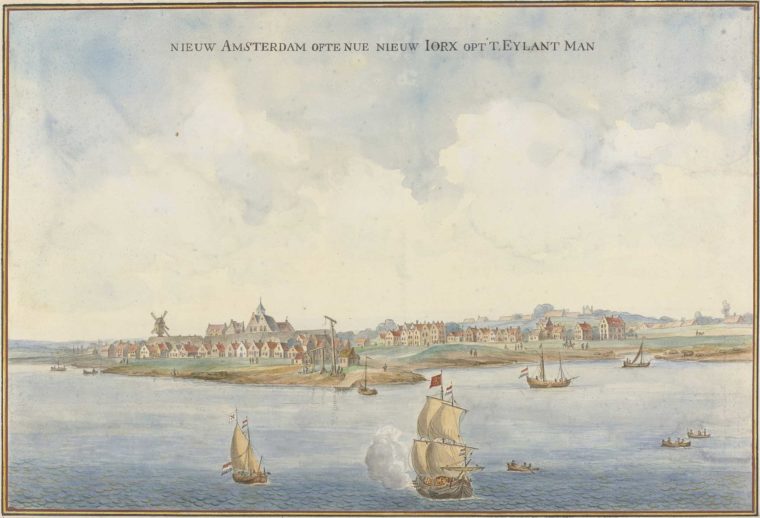

The year 1672 has been recorded in historical literature as the ‘rampjaar’ or the year of disaster. France attacked the Dutch Republic and it took the Dutch great efforts to defeat the French on land. Meanwhile, overshadowed by this catastrophe, there was a remarkable achievement taking place on the other side of the Atlantic Ocean, the conquest of New York in 1673 by the Cornelis Evertsen the Younger, who came from Zeeland.

Cornelis Evertsen de Younger (1642-1706) was vice-admiral of the Republic’s fleet when he received the command to conquer Saint-Helena in 1672. The island of Saint Helena, located in the southern Atlantic Ocean, belonged to the English. Vice-admiral Evertsen was supposed to capture the island with six ships and was ordered to overpower English who would later sail to the East Indies but whom now resided on the island. At the time, the Republic was at war with England; this was already the third Anglo-Dutch war which would last from 1672 to 1674.

When Evertsen arrived, ships belonging to the Dutch East India Company (VOC) had already conquered the island. Evertsen therefore decided to sail on to the Carribean, more specifically he went to Cayenne which was part of French Guyana. This destination was mentioned in his assignment as alternative to his primary objective of Saint Helena. Evertsen, however, deemed his fleet too weak to be able to attack Cayenne and decided to join a fleet from Holland in the Caribbean. This fleet under the command of Jacob Benckes, who was on his way to Virginia.

Capturing ships on the Hudson river

21 ships reached the Hudson river in August 1673. Eleven ships were overpowered and claimed as a trophy while still in the river. Evertsen received information from Dutch farmers about fort Jems (James), located on the island of Manhattan, which was apparently badly defended. He decided to attack the fort the following day. The States General of the Netherlands notified the citizens of New York of current events.

In the morning of August 9th 1673, a trumpeter was send to the fort demanding their surrender. That same afternoon, three Englishmen boarded Cornelis Evertsen the Younger’s ship the Swaenenburgh. Boarding the ship that afternoon were Thomas Lovelace, the brother of governor Francis Lovelace, Captain John Carr and attorney John Sharpe. These were the representatives of the fort’s commander Captain John Manning.

The assignment ‘in the canon’s barrel’

The three men asked Evertsen where he came from. The vice-admiral, who was a hotheaded individual and therefore earned the nickname of ‘little Cornelis the devil’ responded that they should be able to recognize his origin from the flags on his ships. The Englishmen then wanted to know with what kind of assignment (commisie) he had that allowed him to enter the river of the duke of York, and asked to see his assignment letters. Evertsen responded that “it was stuck in the barrel of the canon, which could become dangerous if the fort would not surrender.” (“dat die in de tromp van ’t canon stack, gelijc sij welhaest souden gewaer worden, bij aldien het fort niet overleverden”.)

Meanwhile, the trumpeter returned to the ship with a message from Captain Manning, which noted that he would respond once he had spoken to Lovelace, Carr and Sharpe. The three men requested Evertsen to hold off his attack until discussed matters with Manning. The Vice-admiral agreed, on the condition that they would return with an answer within thirty minutes. Sharpe kept his promise and returned with a message from Manning which stated that he wanted to convene with the mayors and councilmen of New York before proceeding.

New York becomes Nieuw Orangien

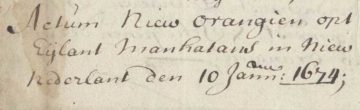

Evertsen feared that the commander was stalling in order to summon soldiers from elsewhere to the fort. He ordered Manning to surrender the fort within half an hour in name of The States General of the Netherlands. After waiting another 30 minutes, the war fleet opened fire and soldiers using boats and sloops, moved to the shore. The fort’s flag was soon taken down and replaced by a white flag. Fort Jems (James) was conquered and was renamed Fort Willem Hendrik. New York was renamed New Orangien, and the province consisting of three islands, three cities and dozens of villages, was renamed New Netherlands (Nieuw Nederland).

Grateful citizens of Manhattan

The citizens seemed very pleased with the takeover. In September 1673, the bailiff, mayors and the board of aldermen of New Orangien of the island of Manhattan, wrote a long letter to the State of Zeeland. The authors of this letter were bailiff Anthonij de Mill, mayors Johannes de Peijster, Aegidius Luijk and Johannes van Burgh and finally Willem Beeckman, Jeronimus Ebbinck, Jacob Kip, Laurens van de Spighel and Guilain Verplanck who were all members of the board of aldermen.

In this letter, the men thanked Zeeland from the bottom of their hearts and they assured the provincial government that they would only benefit from this takeover. For instance, ““veele particuliere familien die door den ovevall der francen sijn geruineert, sigh hier te lande seer gemackelijck sullen connen erneren.” In other words, inhabitants of the Republic who lost their belongings due to the invasion of the French, could easily satisfy their needs in New York.

Benefits for Zeeland

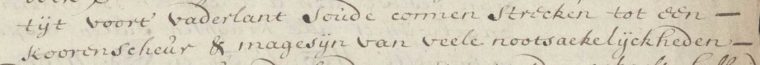

New Orangien, as argued by the city council, had potential to become ‘a barn and depository of many necessities’ (‘een koorenscheur & magesijn van veele nootsaeklijckheden’) for the province of Zeeland. After the takeover, New Orangien could even provide the province’s colonies of Suriname and Curacao with provisions.

Additionally, the council also recommended the city as base to sell captured enemy ships from and as station to supply warships from in times of war. However, New Orangien’s most important new asset was the possibility of keeping an eye on England. If the English King would be the sole ruler of the northern part of America, he would be able to supply ships from this location without drawing attention on the European continent, and therefore he would be able to unexpectedly attack the Dutch republic or its allies. (‘Als de koning van Engeland alleenheerser “van dit noorder gedeelte van America” zou worden, dan zou hij “buijten weten van eenig prins off potentaet in Europa alhier eenige scheepen equiperen & soo op ’t onverwagst, onsen staet of haere bontgenooten overvallen.’”) Finally, the city was also ideal for trading opportunities such as the pelting industry or the tobacco industry. (“‘den bever & pelterij handell tot onderhoudinge van de negotie in Muscovien’ of de tabakshandel.”)

Nieuw Orangien calls for aid from Zeeland

Unfortunately, the newly conquered area which provided so many profitable opportunities for Zeeland, still had to be protected against invasions from the English and/or the French. Help urgent for the ‘good citizens of the nation’ who in a letter send to the province of Zeeland were estimated to consist of seven thousand citizens including women and children. Zeeland was requested to send men and materials to defend its conquest. A proposal in accordance with this request was send back to Europe.

In September 1673, a citizen called Cornelis van Ruijven, who had held several renown positions, was sent back to the Republic with this particular message conveyed in this letter. Unfortunately, van Ruijven did not reach his destination. His ship had to sail through bad weather conditions, was then captured and eventually resold in New England. Once the news was received by the bailiff, mayors and the board of aldermen, they immediately wrote another letter. They replicated their first letter and added a new letter on the same paper. In this second letter, dated January 10th 1674, they urgently called upon the provincial council of Zeeland for support once again.

Zeeland wants to get rid New Orangien

Meanwhile, the news regarding the conquest of New York had already reached the Republic. The admiralty of Amsterdam received word in October 1673, who in turn informed the States General of the Netherlands and on November 9th an assessment of the situation was made during a meeting of the States of Zeeland.

Zeeland was unhappy with their new acquisition. The expensive ‘rampjaar’ (year of disaster) had only just ended and in addition to this, they also had to deal with another costly conquest: Suriname, which was conquered by Zeeland in 1667 by Abraham Crijnssen. However, instead of being beneficial, the colony became an expensive resource which had cost more money than it brought in.

The admiralty of Amsterdam and the admiralty of Zeeland shared interests in conquering New York. However, The States General of the Netherlands preferred Amsterdam governing Nieuw Nederland (New Netherlands).

In January 1674, the States of Zeeland send representatives to Holland in order to find out

whether Amsterdam actually claimed governing rights over ‘Nieuw Nederland’. In this case, the representatives would notify Amsterdam that Zeeland would be prepared to transfer their share including its burdens and benefits, in exchange for some profits. If Amsterdam wished to share the governing tasks of ‘Nieuw Netherland’, the representatives would stress their wish to retreat from ‘Nieuw Nederland’. Nevertheless, Zeeland had also considered a third option: if some citizens of Amsterdam wished to take over New York, the province would gladly cooperate.

New Orangien becomes New York again

When Cornelis Evertsen the Younger returned to Zeeland in July 1674, he did not receive a warm welcome. He was accused of forsaking his assignment, which was to conquer Saint-Helena and/or Cayenne. He also never should have shared the profits from the ships that were captured during the journey and in the Hudson river with the people from Holland.

At that time, New York or New Orangien had already fallen back into English hands. At the end of the third Anglo-Dutch war, the area was officially handed over to the English in the treaty of Westminster in February 1674.

Journal and letters in the Zeeland Archives

The ship’s log of the Swaenenburgh, the flagship of Cornelis Evertsen the Younger, has been preserved in the Zeeland Archives, just like the letters of the vice-admiral; the council of New York and the council of Cadiz. Zeeland Archives, Collection Handwritings, Rijksarchief in Zeeland, toegang 33.1, inv.nr 83.

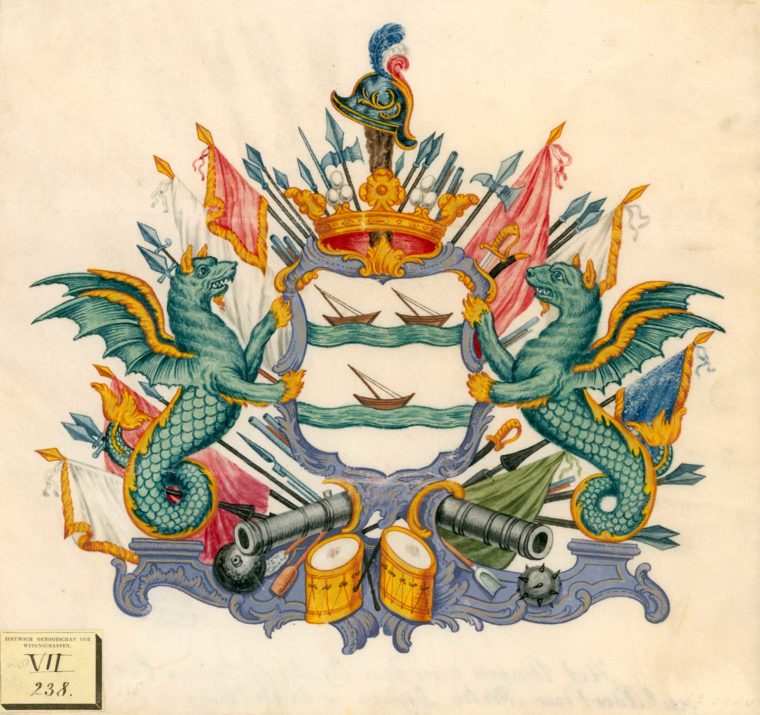

www.archieven.nlThe memorable events of 1673 were recorded in the cartouche of a map published in 1674 by Hugo Allard: Allard -Totius Neobelgii Nova et Accuratissima Tabula.

Publication of the source material of the journal

The journal which records the journey of the Swaenenburgh, the flagship of Cornelis Evertsen the Younger, including transcriptions of the source material, has been published in 1928. This publication by the Linschoten-Vereeniging is available online at the website of the Geheugen van Nederland (the cultural Memory of the Netherlands).

resolver.kb.nl